Largest-Ever Analysis of Ketamine Therapy for Sleep Shows 77% Response Rate Among 13,963 Mindbloom Patients

Summary:

Mindbloom conducted the largest retrospective real-world analysis of ketamine therapy for sleep to date, in which 13,963 patients reported outcomes matching or exceeding those reported in many studies of conventional sleep medications and psychotherapy.

Highlights:

- Response rate: 77% of patients reported clinically meaningful sleep improvement (defined as ≥1-point improvement on PHQ-9 item 3)

- Magnitude of relief: On average, patients reported a 49% improvement in sleep disturbances

- Tolerability: 95% did not report side effects during treatment, with only 2.5% reporting any worsening of sleep disturbances

Methodology:

- Study Population: 13,963 patients who had moderate to severe sleep disturbances at baseline, defined as scores of 2 ("more than half the days") or 3 ("nearly every day") on PHQ-9 item 3. Mean baseline score was 2.55

- Treatment Protocol: Six guided at-home ketamine sessions completed over four to six weeks, supported by structured preparation, integration, and continuous clinician monitoring

- Outcome measure: Sleep disturbance was assessed using PHQ-9 item 3 ("Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much"), a validated single-item measure directly capturing sleep disruption frequency. This item is widely used in clinical research and scored on a 4-point scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, 3 = nearly every day)

How effective is Mindbloom ketamine therapy for sleep?

Among the 13,963 Mindbloom patients analyzed, 79% reported at least a 1-point reduction on PHQ-9 item 3, which represents clinically meaningful improvement in self-reported sleep disturbance. Sleep scores improved 49% on average, suggesting considerable depth of improvement in addition to the breadth of those who responded.

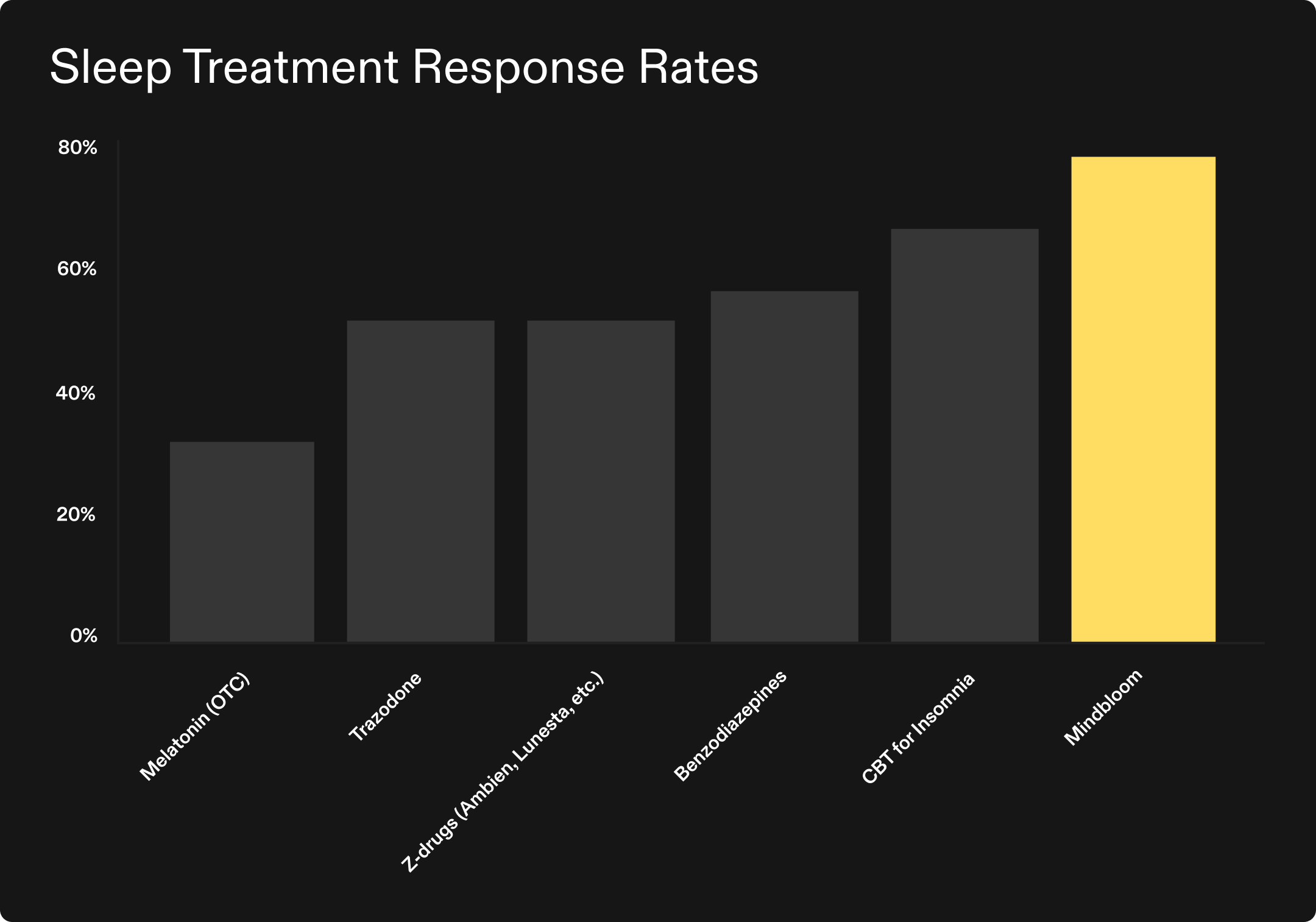

To contextualize our findings, researchers applied validated anchor-based and distribution-based methods to compare response rates. Researchers mapped Mindbloom's PHQ-9 item 3 threshold against published data from conventional sleep treatments using different outcome measures, including the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and MADRS item 41,2. Using this standardized comparison framework, Mindbloom's response rate was:

- Up to 137% higher than melatonin study estimates3, 4, 5

- Up to 47% higher than Z-drug6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and Trazodone11, 12, 13 study estimates

- Up to 34% higher than Benzodiazepine study estimates14, 15

- Up to 14% higher than Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT-I) study estimates16, 17, 18, 19

This analysis suggests that Mindbloom’s at-home ketamine therapy may produce response rates exceeding those seen in studies of conventional medications, and comparable to or exceeding those seen in studies of the gold standard therapeutic approach.

Comparisons synthesize published data across randomized trials and real-world studies. See the full white paper for detailed methodology and sources. No head-to-head trials performed.

How safe is Mindbloom ketamine therapy for sleep?

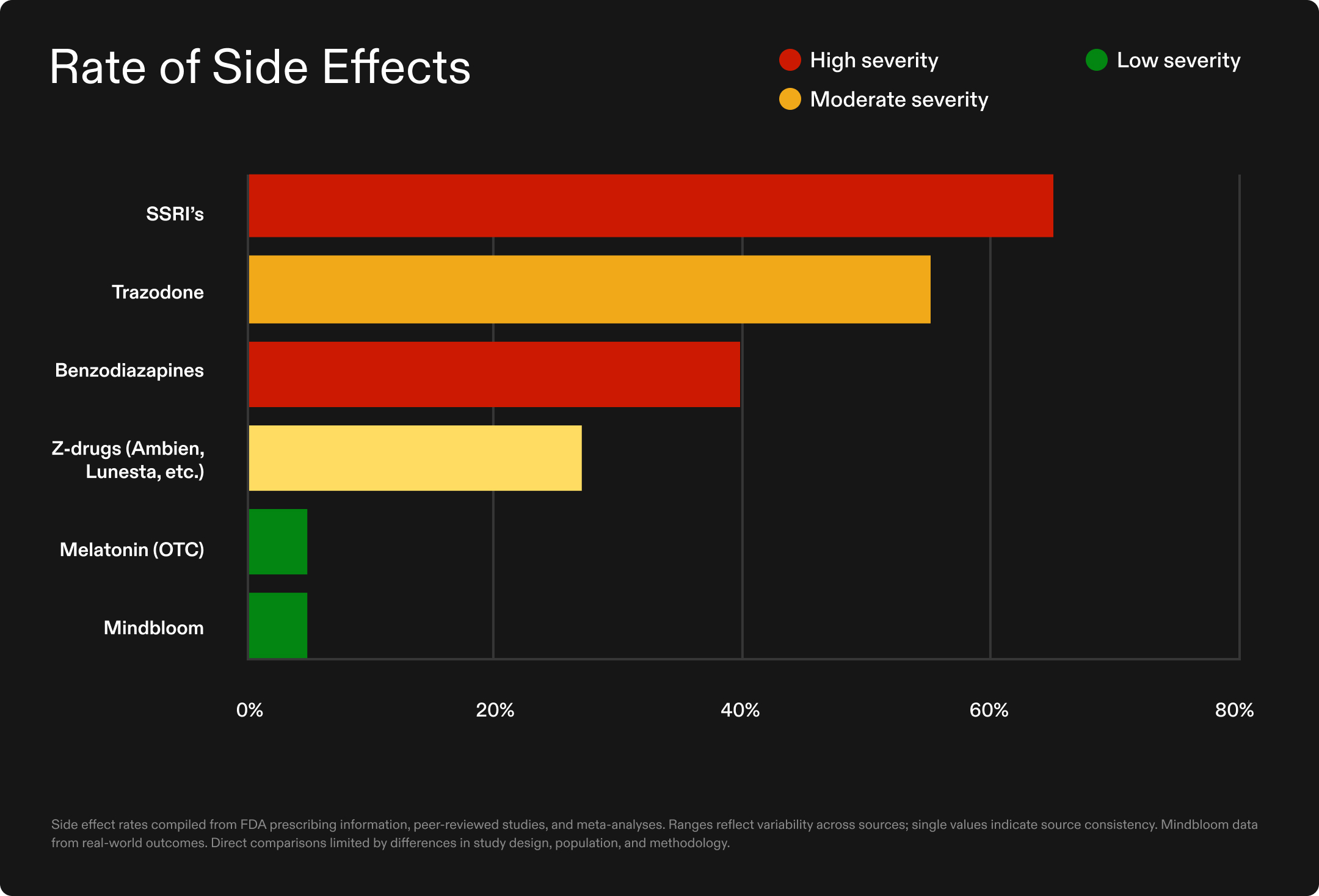

Tolerability was notably high across the Mindbloom cohort. Of the 13,963 clients analyzed, 95% did not report side effects during their treatment course. When side effects did occur—in just 5% of participants—they were typically mild and transient, including memory changes, GI discomfort, blood pressure changes, and headache.

Importantly, only 2.5% of participants reported that their sleep worsened during treatment, indicating that the intervention rarely led to deterioration of the primary concern.

This safety profile contrasts sharply with conventional sleep medications:

- Benzodiazepines carry dependency risks, with up to 23% of users becoming dependent within three months20, plus increased fall and fracture risk21

- Z-drugs, (like Ambien and Lunesta), have been linked to 63% increased fracture risk22 and higher rates of motor vehicle collisions23

- SSRIs have been linked to 60–70% higher insomnia likelihood in depression treatment24

- Over-the-counter melatonin faces quality control issues, with 40% of U.S. products failing to meet acceptable dosing standards.25

In addition, many sleep medications also suppress the deep and REM sleep stages critical for memory consolidation and physical recovery26, offering unconsciousness but potentially impacting restoration.

Which ketamine therapy protocol produces better sleep outcomes: at-home or in-clinic?

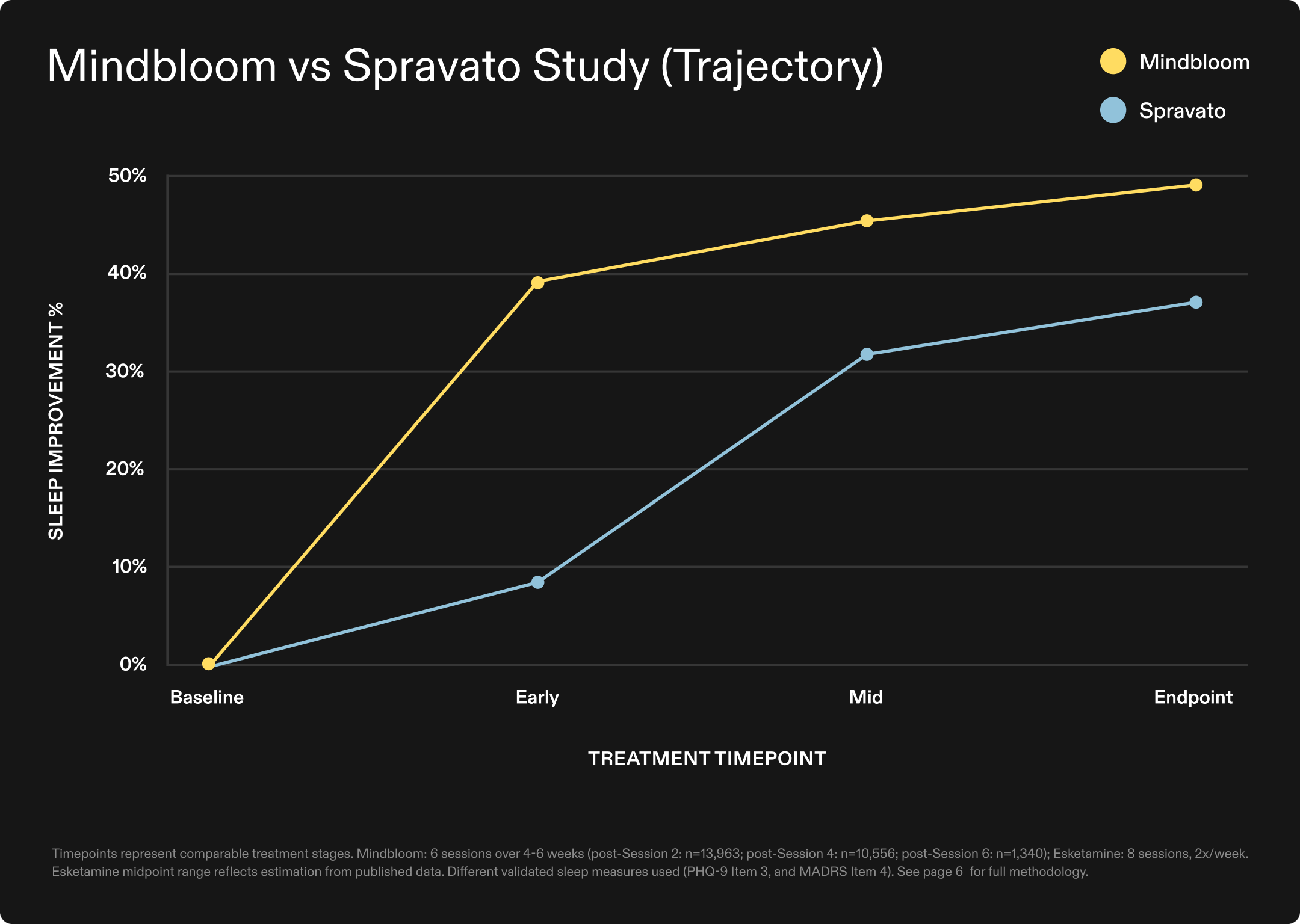

While clinical research on ketamine therapy for sleep remains nascent relative to other psychiatric conditions, comparative analyses of different treatment protocols provide valuable insights into what may drive efficacy. This analysis examined two fundamentally different delivery approaches—at-home ketamine therapy with less frequent dosing versus clinic-based esketamine given more frequently31. At endpoint, Mindbloom patients in this analysis reported an average 49% improvement in sleep disruption, compared to 38% reported in a published esketamine study—suggesting faster response with fewer, less frequent total sessions.

The findings suggest that treatment accessibility and protocol efficiency need not be sacrificed for clinical efficacy, challenging the conventional assumption that intensive clinic-based administration is necessary for therapeutic benefit.

*This comparison maps Mindbloom's actual outcome data across measurable treatment stages against published esketamine outcomes at comparable treatment timepoints, with midpoint estimates derived from available published data where direct comparisons were not possible.

Why is sleep disruption such a pressing issue?

Sleep disorders affect 50 to 70 million Americans27—more than diabetes, asthma, or depression. The health consequences extend far beyond fatigue: disrupted sleep significantly increases risk of cardiovascular disease28, type 2 diabetes29, and early mortality while impairing memory, weakening immunity, and accelerating cognitive decline30.

The result: millions cycling through interventions that either don't work or risk long-term health concerns. Sleep deprivation costs the U.S. economy over $400 billion annually30, but the true cost is measured in diminished quality of life and suffering that compounds over time.

What does this analysis add to the field?

This real-world analysis joins the growing body of Mindbloom-led research—including Hull et al., 2022, Journal of Affective Disorders and Mathai et al., 2024, Journal of Affective Disorders—the two largest peer-reviewed studies of ketamine therapy published to date. With findings now spanning depression, anxiety, PTSD, and sleep, our results reflect not just what we believe is possible, but what our patients are actually experiencing. In a landscape where claims often outpace evidence, we've chosen a different path: publish the data and let the results speak.

Healing should not require sacrificing time, comfort, or financial stability. Mindbloom's at-home model makes evidence-based treatment accessible at a fraction of the cost of clinic-based alternatives—bringing the possibility of relief to the millions for whom sleep dysfunction has gone unaddressed for too long.

Read and download the full analysis, methodology, and statistical details here.

Want to learn more about at-home ketamine therapy?

- To learn more about Mindbloom's at-home ketamine therapy, visit our homepage.

- If you're ready to explore at-home ketamine therapy, take our brief candidate assessment.

- Read additional research on how ketamine therapy may help with depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

- For safety information about ketamine, click here.

- Questions about Mindbloom? Reach out to our client relations team at support@mindbloom.com.

Citations:

- Yang M, Morin CM, Schaefer K, Wallenstein GV. Interpreting score differences in the Insomnia Severity Index: using health-related outcomes to define the minimally important difference. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25(10):2487-2494. doi:10.1185/03007990903167415

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34(5):601-608. doi:10.1093/sleep/34.5.601

- Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0063773

- Besag FMC, Vasey MJ, Lao KSJ, Wong ICK. Adverse events associated with melatonin for the treatment of primary or secondary sleep disorders: a systematic review. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(12):1167-1186. doi:10.1007/s40263-019-00680-w

- Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. Nightly treatment of primary insomnia with prolonged release melatonin for 6 months: a randomized placebo controlled trial on age and endogenous melatonin as predictors of efficacy and safety. BMC Med. 2010;8:51. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-8-51

- De Crescenzo F, D'Alò GL, Ostinelli EG, et al. Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for the acute and long-term management of insomnia disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2022;400(10347):170-184. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00878-9

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1335-1350. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0251-z

- Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169. doi:10.1136/bmj.38623.768588.47

- Morin CM, Edinger JD, Beaulieu-Bonneau S, et al. Effectiveness of sequential psychological and medication therapies for insomnia disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1107-1115. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1767

- Ancoli-Israel S, Krystal AD, McCall WV, et al. A 12-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effect of eszopiclone 2 mg on sleep/wake function in older adults with primary and comorbid insomnia. Sleep. 2010;33(2):225-234. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.2.225

- Walsh JK, Erman M, Erwin CW, Jamieson A, Mahowald M, Regestein Q, Scharf M, Tigel P, Vogel G, Ware JC. Subjective hypnotic efficacy of trazodone and zolpidem in DSMIII-R primary insomnia. Hum Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(3):191-198. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1077(199804)13:3<191::AID-HUP972>3.0.CO;2-X

- Yi XY, Ni SF, Ghadami MR, Meng HQ, Chen MY, Kuang L, Zhang YQ, Zhang L, Zhou XY. Trazodone for the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Sleep Med. 2018;45:25-32. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2018.01.010

- Kokkali M, Pinioti E, Lappas AS, Christodoulou N, Samara MT. Effects of trazodone on sleep: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CNS Drugs. 2024;38(10):753-769. doi:10.1007/s40263-024-01110-2

- Nowell PD, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, Dew MA, Reynolds CF 3rd, Kupfer DJ. Benzodiazepines and zolpidem for chronic insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. JAMA. 1997;278(24):2170-2177

- Thamayanthi K, Vasanthira, Kulandaiammal, Hemavathi, Jeyalalitha. Sleep pattern and sleep quality observed with Tab. Diazepam and Tab. Alprazolam in patients treated for insomnia. IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2017;16(4):136-142. doi:10.9790/0853-160408136142

- Morin CM, Vallières A, Guay B, Ivers H, Savard J, Mérette C, Bastien C, Baillargeon L. Cognitive behavioral therapy, singly and combined with medication, for persistent insomnia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(19):2005-2015. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.682

- van Straten A, van der Zweerde T, Kleiboer A, Cuijpers P, Morin CM, Lancee J. Cognitive and behavioral therapies in the treatment of insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;38:3-16. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2017.02.001

- Wu JQ, Appleman ER, Salazar RD, Ong JC. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia comorbid with psychiatric and medical conditions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1461-1472. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.3006

- Geiger-Brown JM, Rogers VE, Liu W, Ludeman EM, Downton KD, Diaz-Abad M. Cognitive behavioral therapy in persons with comorbid insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;23:54-67. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2014.11.007

- Soyka M, Wild I, Caulet B, Leontiou C, Lugoboni F, Hajak G. Long-term use of benzodiazepines in chronic insomnia: a European perspective. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2023;14:1212028. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1212028

- Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG. (2003). "Benzodiazepines and risk of hip fractures in older people: a review of the evidence." CNS Drugs, 17(11):825-837

- Treves N, Perlman A, Kolenberg Geron L, Asaly A, Matok I. Z-drugs and risk for falls and fractures in older adults—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2018;47(2):201-208

- Yang YH, Lai JN, Lee CH, Wang JD, Chen PC. Increased risk of hospitalization related to motor vehicle accidents among people taking zolpidem: a case-crossover study. Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;21(1):37-43

- Zhou S, Li P, Lv X, Lai X, Liu Z, Zhou J, Liu F, Tao Y, Zhang M, Yu X, Tian J, Sun F. Adverse effects of 21 antidepressants on sleep during acute-phase treatment in major depressive disorder: a systematic review and dose-effect network meta-analysis. Sleep. 2023;46(10):zsad177. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsad177

- Pawar RS, Coppin JP, Khanna S, Parker CH. A survey of melatonin in dietary supplement products sold in the United States. Drug Testing and Analysis. 2025;17(8):1176-1185. doi:10.1002/dta.3823. PMID: 39482109

- Pagel JF, Parnes BL. Medications for the treatment of sleep disorders: an overview. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3(3):118-125. doi:10.4088/pcc.v03n0303. PMID: 15014609

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Sleep health. Accessed November 29, 2025. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/education-and-awareness/sleep-health

- Cappuccio FP, et al. "Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies." European Heart Journal. 2011;32(12):1484-1492.

- Harvard Medical School, Division of Sleep Medicine. Sleep and Disease Risk. Available at:https://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/healthy/matters/consequences/sleep-and-disease-risk

- Hafner M, Stepanek M, Taylor J, Troxel WM, van Stolk C. Why sleep matters—the economic costs of insufficient sleep: a cross-country comparative analysis. Rand Health Q. 2017;6(4):11. PMID: 28983434; PMCID: PMC5627640

- Borentain S, Williamson D, Turkoz I, Popova V, McCall WV, Mathews M, Wiegand F. Effect of sleep disturbance on efficacy of esketamine in treatment-resistant depression: findings from randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2021;17:3459-3470. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S339090

This article is for informational purposes only and is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. Always talk to your doctor about the risks and benefits of any treatment. If you are in a life-threatening situation, call the National Suicide Prevention Line at +1 (800) 273-8255, call 911, or go to the nearest emergency room.

More articles